Fewer L.A. County children died of abuse in 2014

Far fewer Los Angeles County children died because adults had neglected or abused them in 2014, leaving elected officials and experts encouraged — and pondering why.

The number killed dropped from 61 in 2013 to 32 last year as county officials continued an overhaul of the safety net for children, including more training for social workers and an increased emphasis on safety that has resulted in an increase in the number of children removed from their parents to be placed in foster care.

Officials cautioned that the tally might still inch up slightly as they await additional reports from the coroner, but it appeared likely that last year would have the fewest recorded abuse and neglect fatalities since 2008, when a state law required the county to begin releasing the statistics.

“I think it’s pretty clear evidence that we’re on track,” said Los Angeles County Supervisor Don Knabe. He said that years of wrenching stories of child abuse fatalities had led the county to transform and strengthen the Department of Children and Family Services and other county departments meant to support vulnerable children.

Since 2008, critics have hammered county supervisors for what they have characterized as a failure to adequately address repeated child fatality cases that followed egregious errors by social workers. In some instances, social workers disregarded clear signs of abuse and wrote in their notes that severely malnourished children appeared healthy.

Among the 32 who died last year, 21 had previously been reported to social workers as suspected abuse cases through the county’s child abuse hotline, according to data released in response a Times public records act request.

They included 4-year-old Alona Edwards and her 8-year-old brother Eric who died in December when their father deliberately drove the family car at high speed into the back of a parked big-rig. At the time, the father was subject to a long overdue child abuse investigation that was part of a large backlog of incomplete inquiries pending at the Department of Children and Family Services.

David Sanders, a former agency director who led a blue ribbon commission appointed by county supervisors in the wake of the 2013 beating death of 8-year-old Gabriel Fernandez, said he was “ecstatic” about the latest statistics but noted that glaring inadequacies remain in the county’s — and the nation’s — response to abuse.

“A recent research review of FBI records revealed that upwards of one in eight of all homicides is the result of caregiver violence,” said Sanders, who leads a commission appointed by President Obama and Congress to eliminate abuse fatalities.

County supervisors have not done most of the things Sanders recommended. His commission called on them to reduce the backlog of overdue investigations. It also said parenting classes and other services should refocus on people raising children younger than 1 — the most vulnerable population. County supervisors should also better manage contractors overseeing foster parents by linking payments to their ability to show measurable improvements in children’s lives.

But Supervisor Sheila Kuehl said some improvements are already taking hold and may have played a role in last year’s fatality decrease.

She noted that one reason the county has a large backlog of unfinished child abuse investigations is because the county has the state’s highest rate for assigning social workers to investigate reports to the child abuse hotline.

Kuehl also praised the county’s new simulation training for social worker recruits. Trainees enter rooms staged to look like the living rooms of potentially abusive parents and interview actors playing parents who might be hiding evidence of harm.

“These efforts put a huge burden on social workers,” Kuehl said. In recently hiring 750 social workers, the county lowered each investigator’s caseload from 35 to 30. “But that’s still too high,” Kuehl said. She wants the county to keep hiring.

Opinions were divided about whether the county’s most controversial policy change — to remove more children and place them in foster care — helped to reduce deaths.

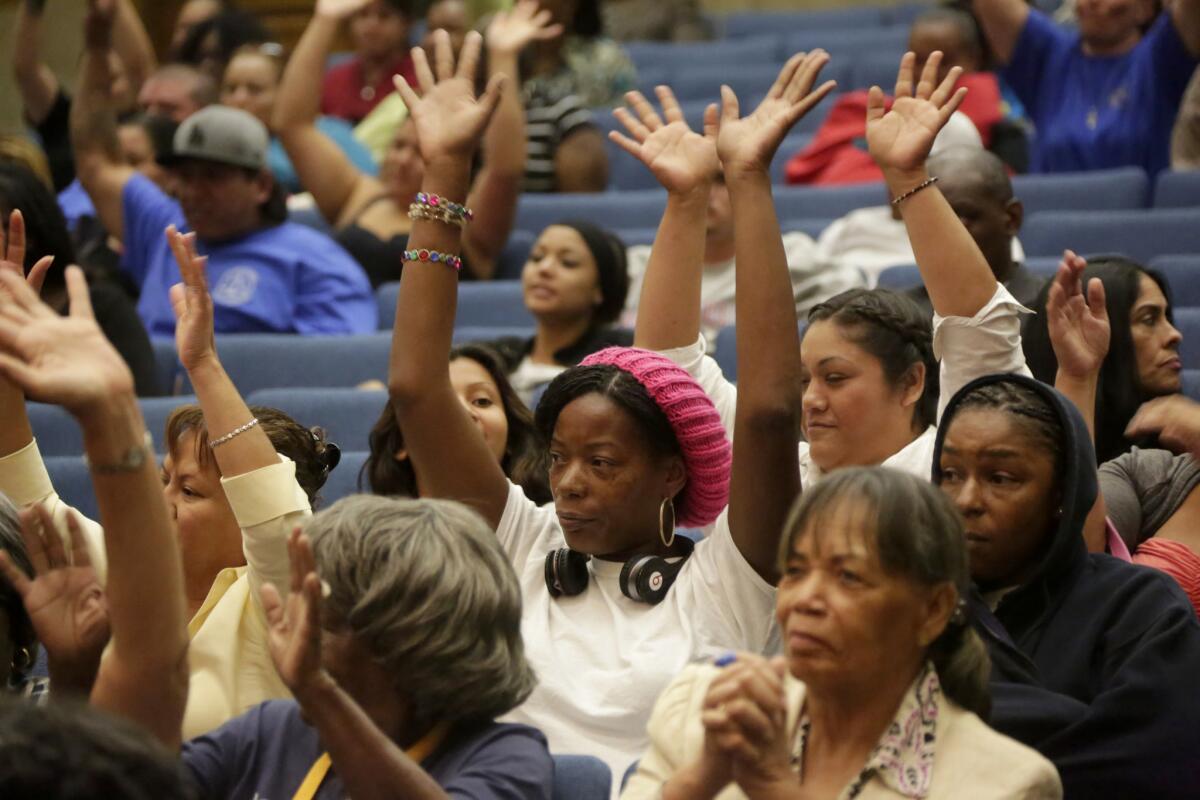

As a result of that change, the number of children in foster care is rising for the first time since the late 1990s. Parent groups believe that the policy allows overzealous social workers to “snatch” children for problems that don’t amount to real abuse, and protested at large rallies at churches in South Los Angeles.

Knabe supports the more assertive approach to removing children from potential danger, calling it a needed antidote to the previous DCFS director’s overemphasis on keeping families together.

Kuehl, however, does not believe that placing more children in foster care is helping.

The solution, she said, is for social workers to identify struggling families before they become dangerous, and to make sure county doctors, therapists and counselors step in to offer more help to the children who aren’t removed from homes.

What matters most to everyone concerned is that fewer children are dying in Los Angeles County. “The question,” Kuehl said, “is whether these deaths went down because the department is doing better, and I think there are signs that it is.”

Follow @gtherolf for breaking news about the foster care system.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.